Mariam Khudikyan

Dear Comrade,

дорогой товарищ

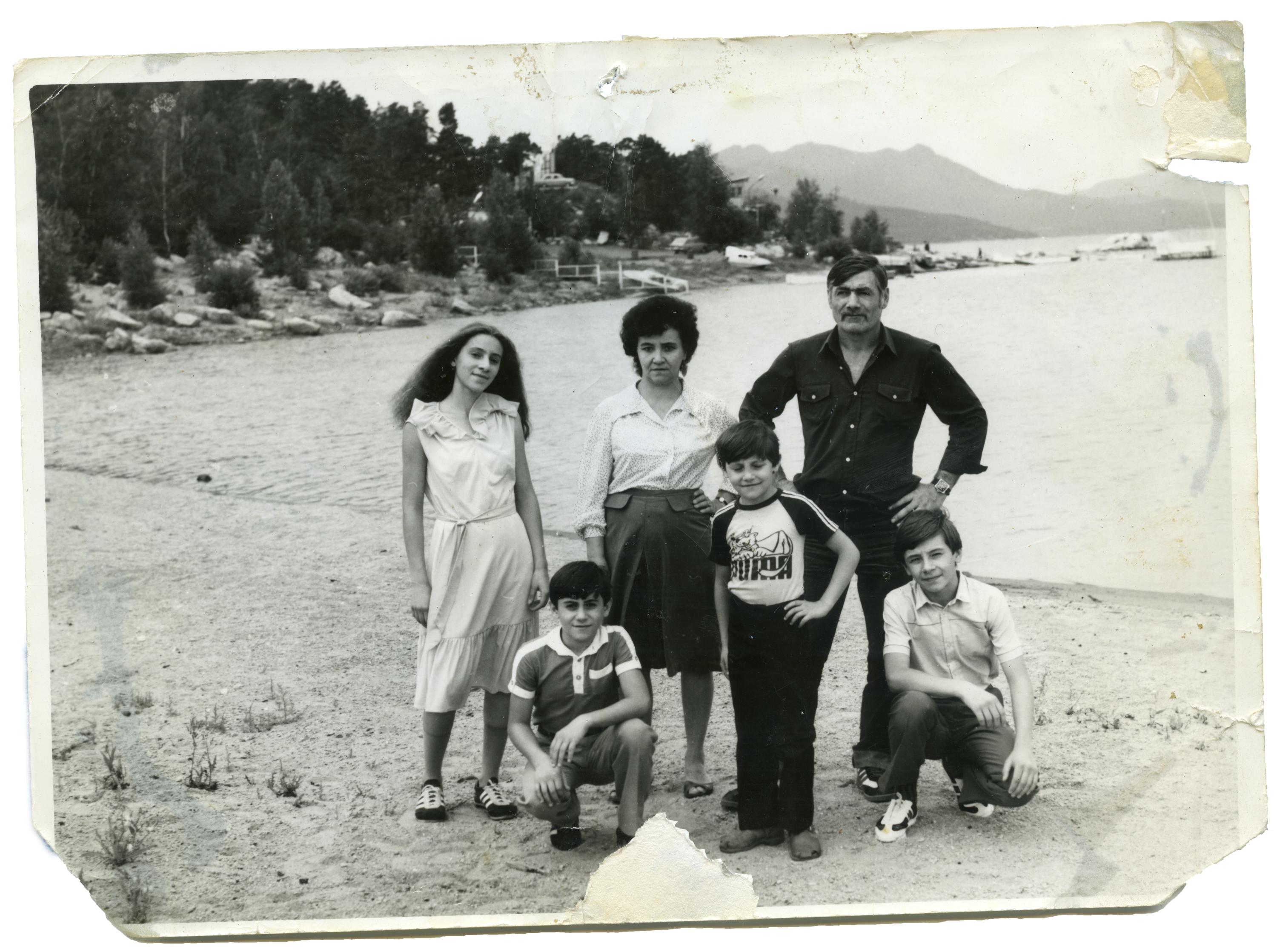

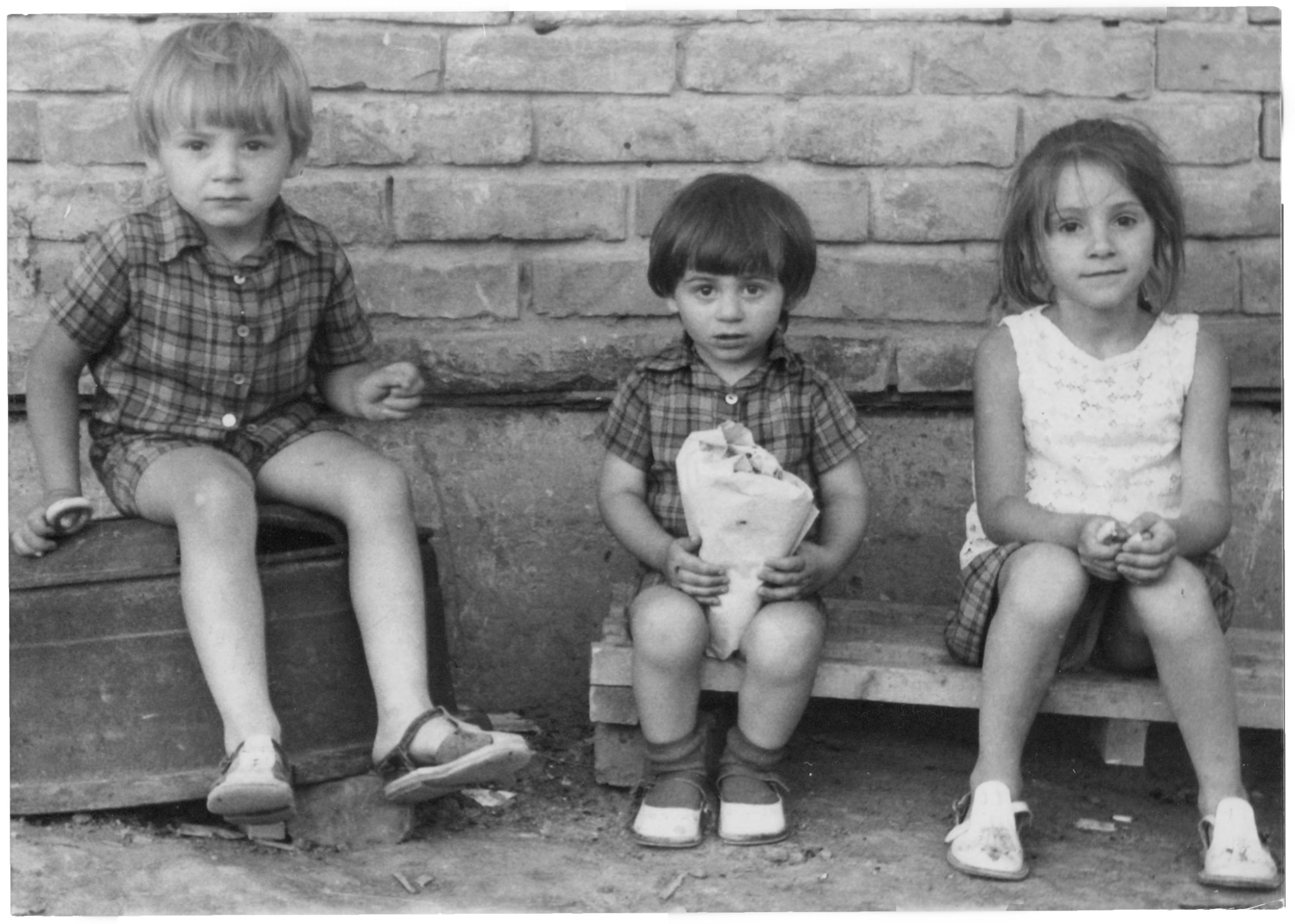

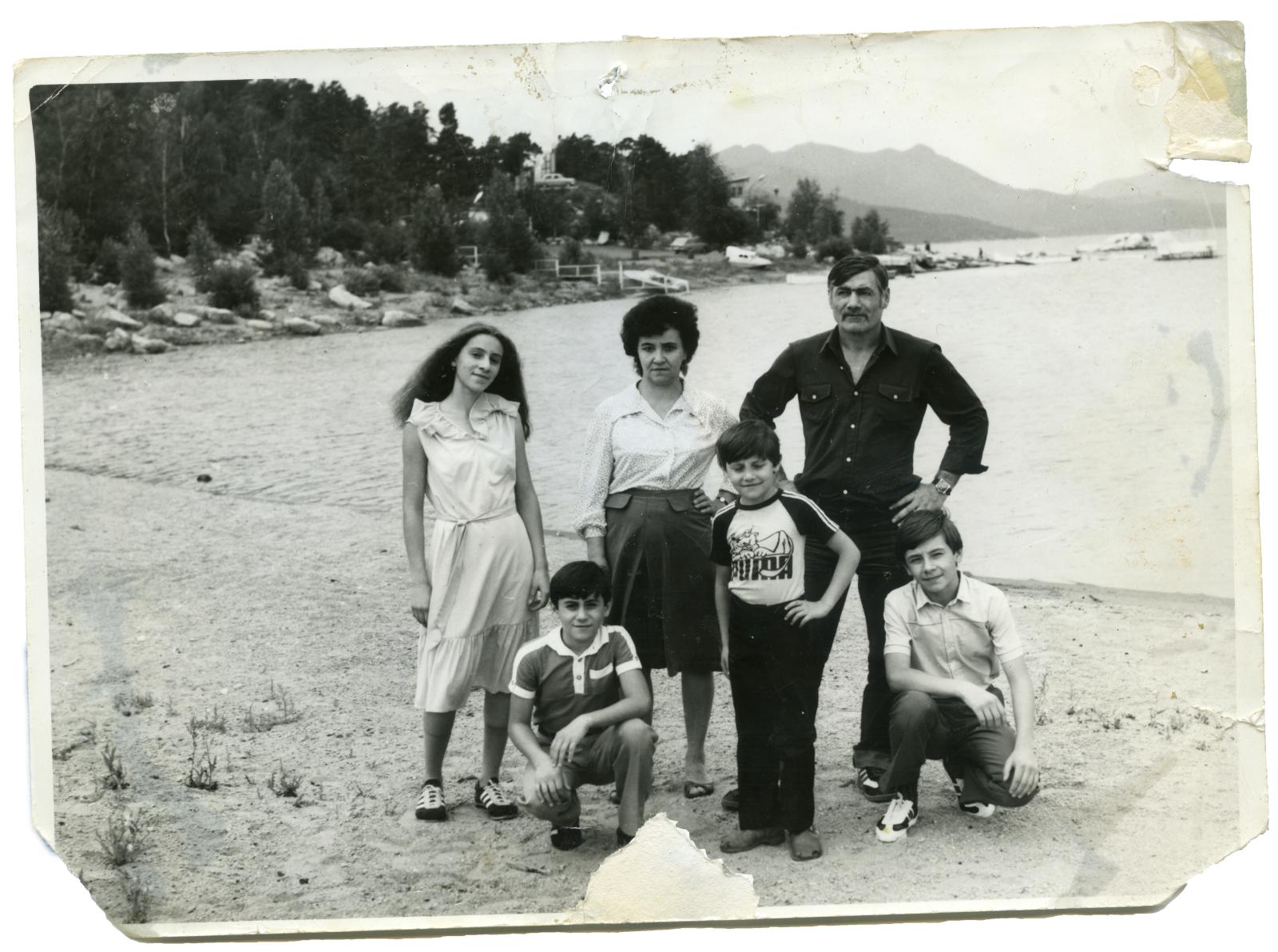

Ongoing: Through family archives, current photos, and written letters, I trace the generational trauma and ideological influence of Soviet Armenia that continues to plague the minds of many Armenians within and beyond their homeland.

Like many post-soviet countries, the environment of Armenia has become a reflection of not only the conflicts that have taken place on the surface, but also in the hearts and minds of its people. Structures from the Soviet era still remain: Grand, Brutalist architecture that once dominated the lands have lost their guise of wealth. Abandoned buildings, worn cars, and dilapidated bunkers are reminders of an era that instilled scarcity and fear. These cold, authoritarian Russian ruins bare a stark contrast to the rich, warm sights that represent an ancient, early Christian Armenia.

Ongoing: Through family archives, current photos, and written letters, I trace the generational trauma and ideological influence of Soviet Armenia that continues to plague the minds of many Armenians within and beyond their homeland.

Like many post-soviet countries, the environment of Armenia has become a reflection of not only the conflicts that have taken place on the surface, but also in the hearts and minds of its people. Structures from the Soviet era still remain: Grand, Brutalist architecture that once dominated the lands have lost their guise of wealth. Abandoned buildings, worn cars, and dilapidated bunkers are reminders of an era that instilled scarcity and fear. These cold, authoritarian Russian ruins bare a stark contrast to the rich, warm sights that represent an ancient, early Christian Armenia.

I

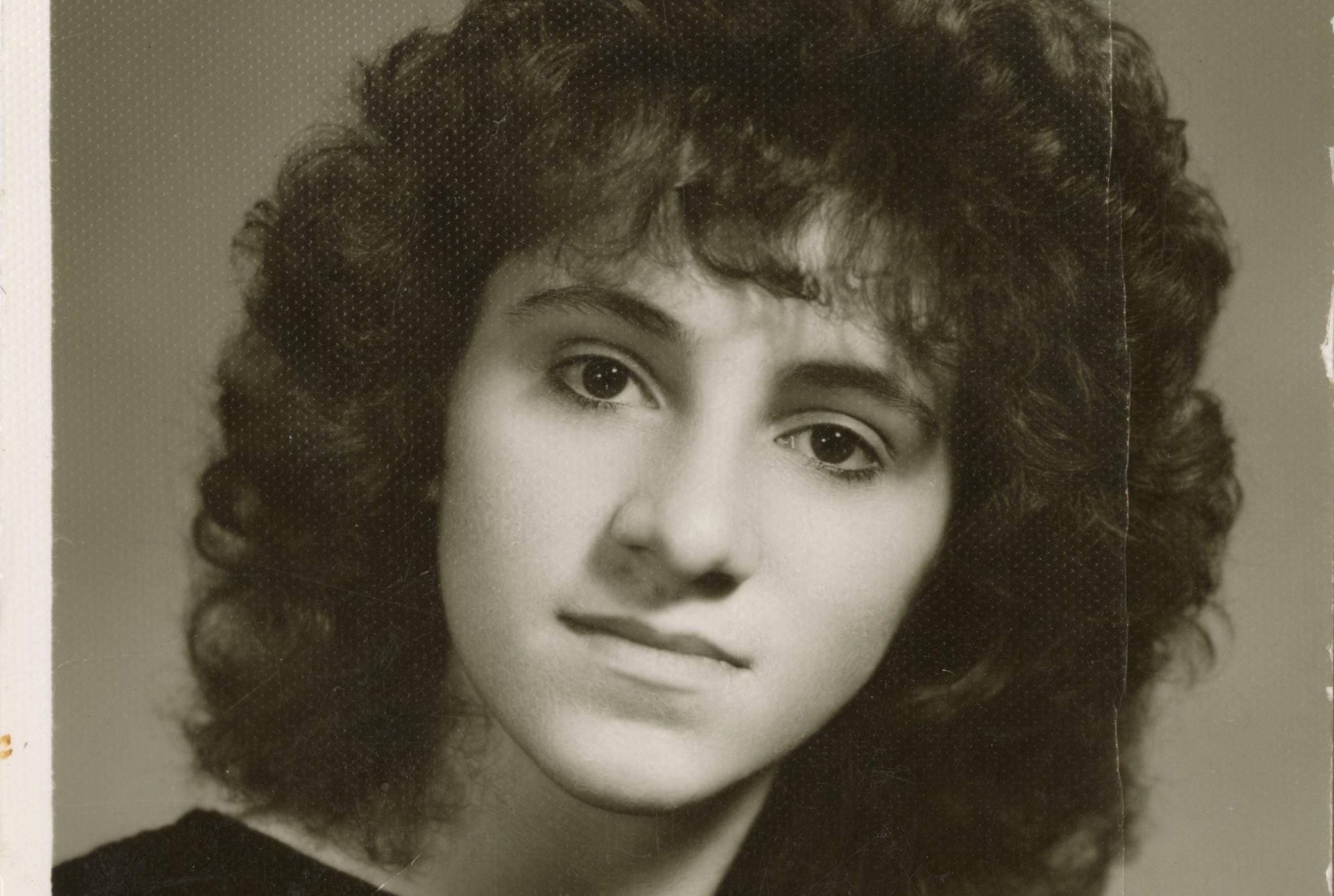

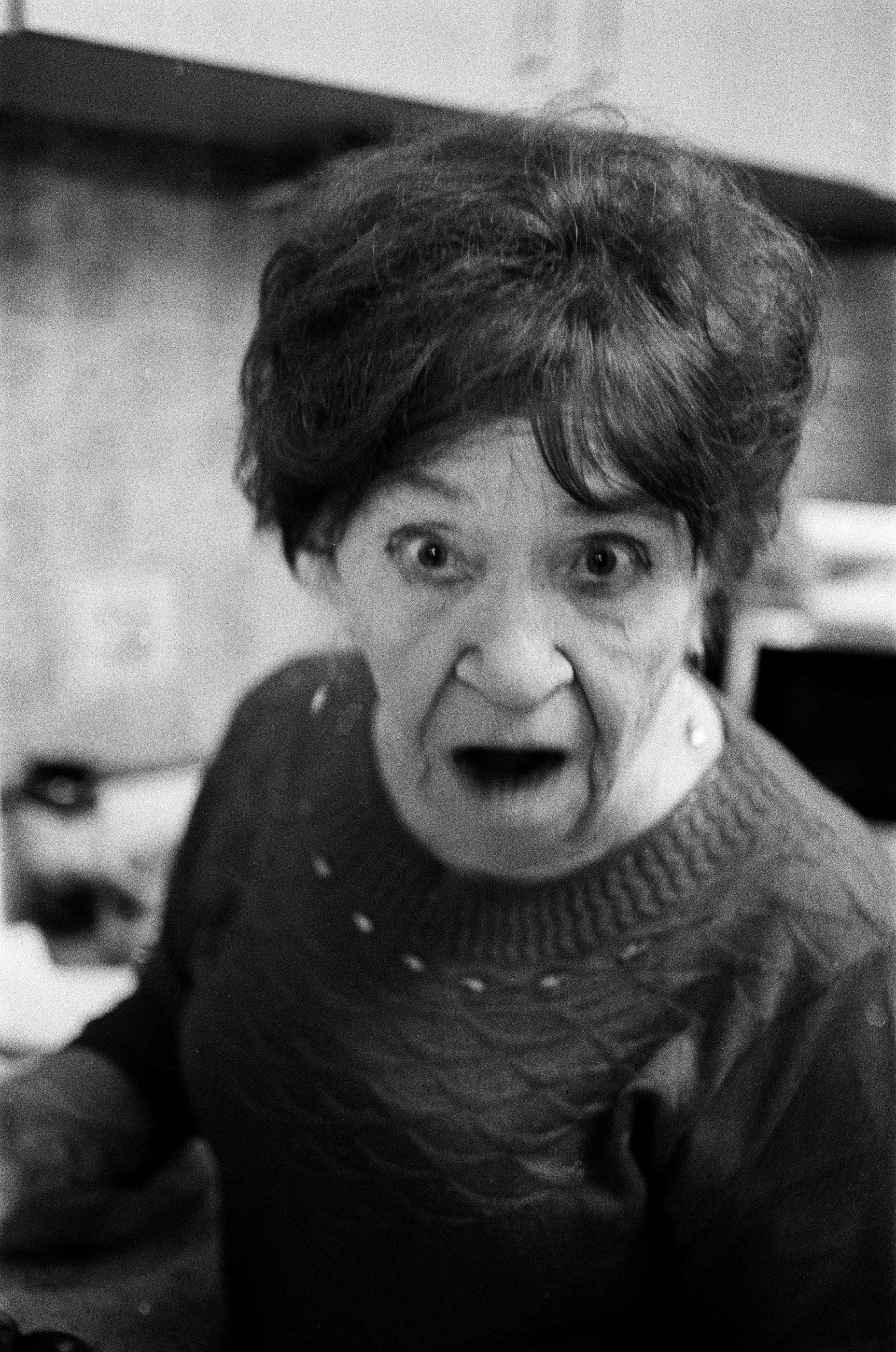

мама

The year is 2025 and the war is not yet over. My mother has not returned to her country since she left in 1990, before the fall of the Soviet Union. When I asked her if she would ever go back she was quick to say no. She says she will never forget when she was surrounded by the tanks, the guns, and the barricades.

She was still pregnant with my sister then. Her birth was complicated. She says the doctors there are no good. She says that could be why my sister turned out the way she did.

She was still pregnant with my sister then. Her birth was complicated. She says the doctors there are no good. She says that could be why my sister turned out the way she did.

II

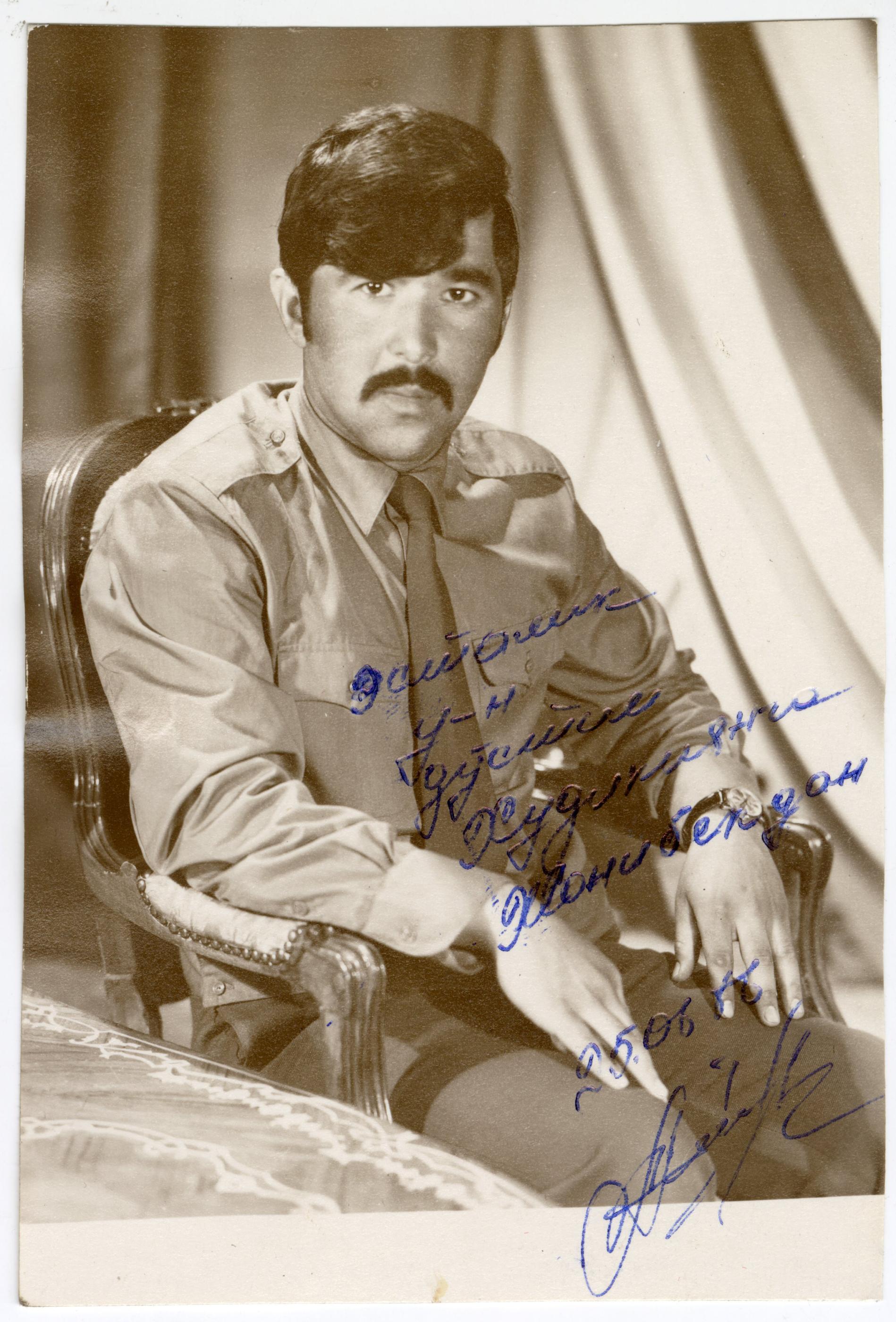

папа

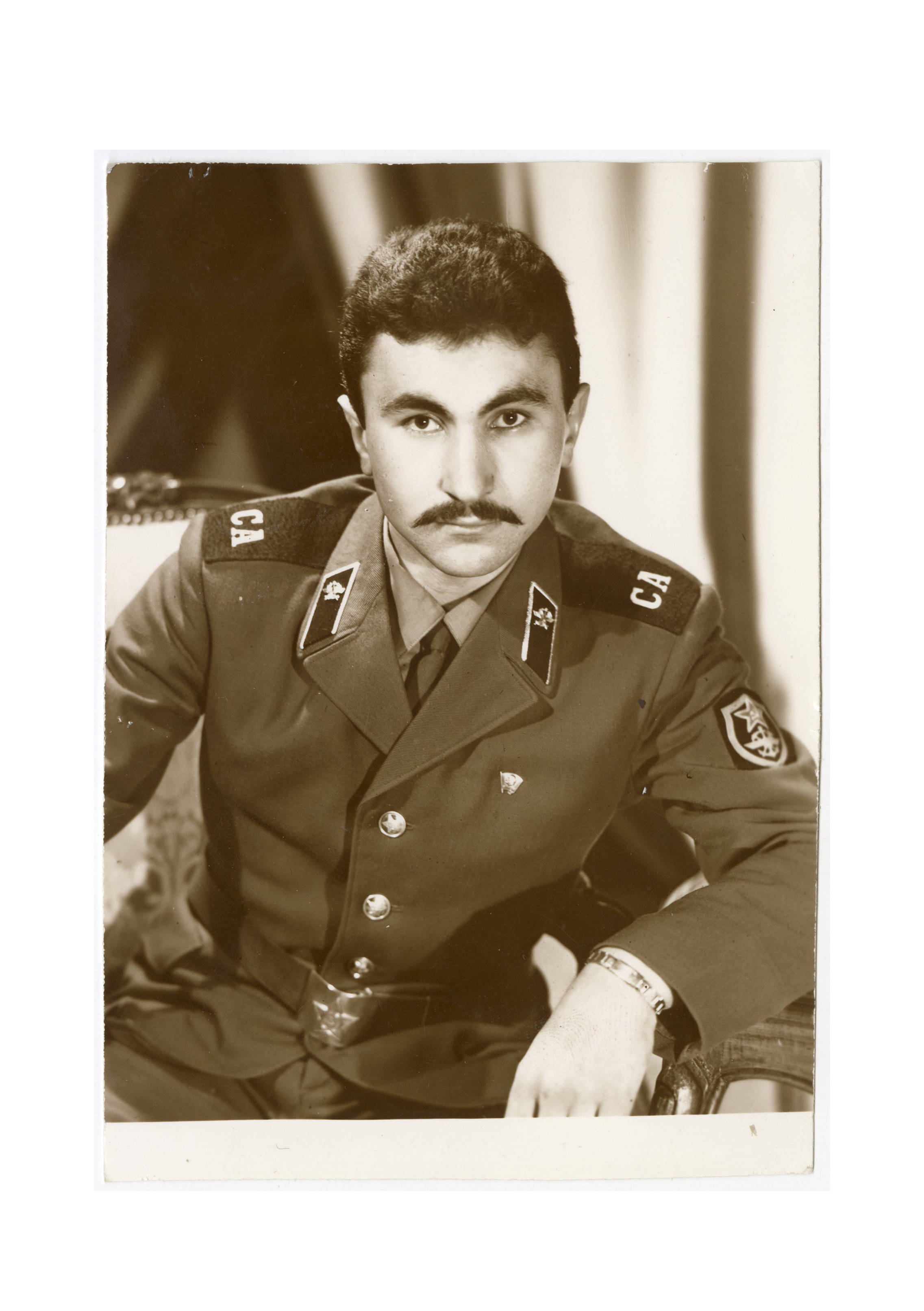

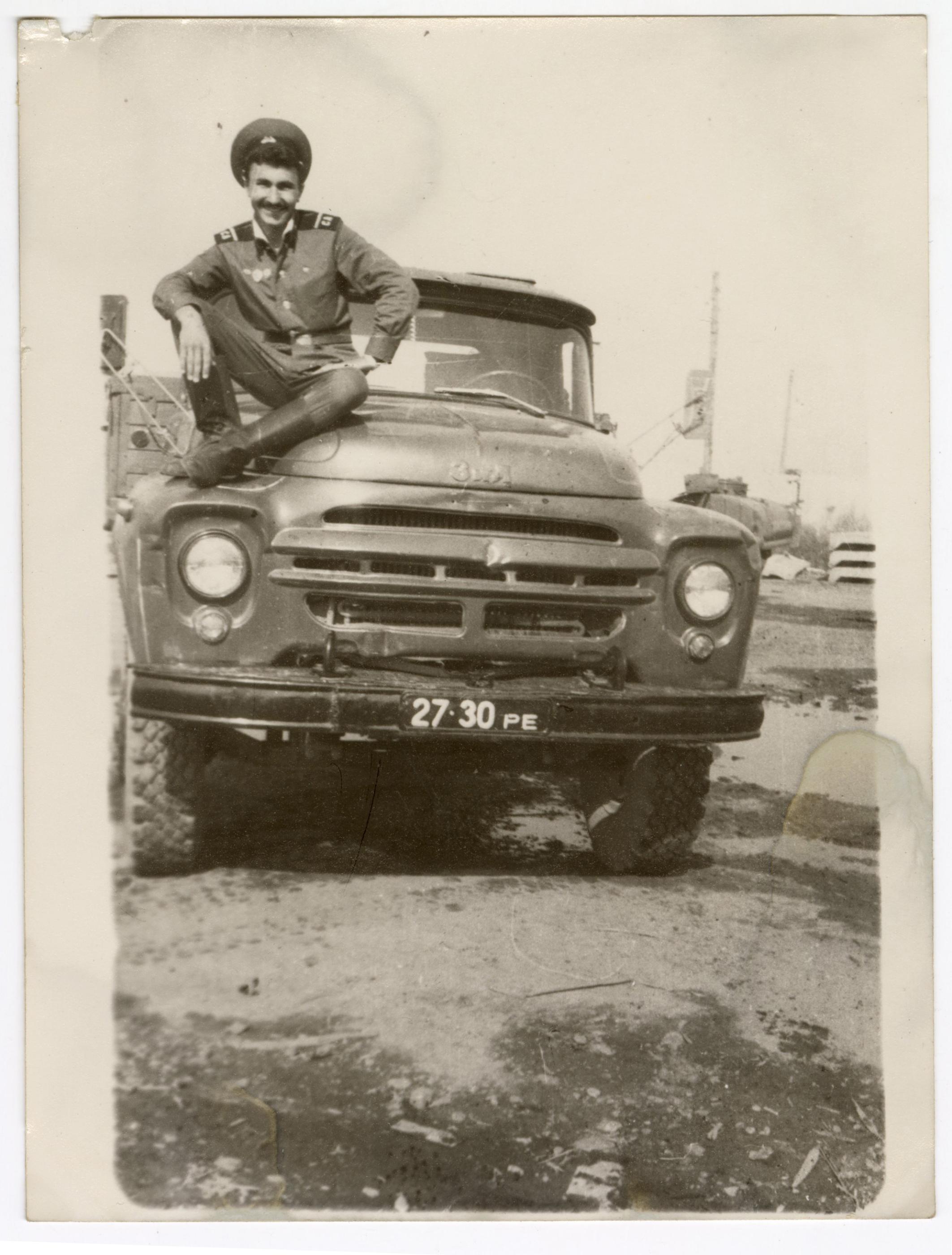

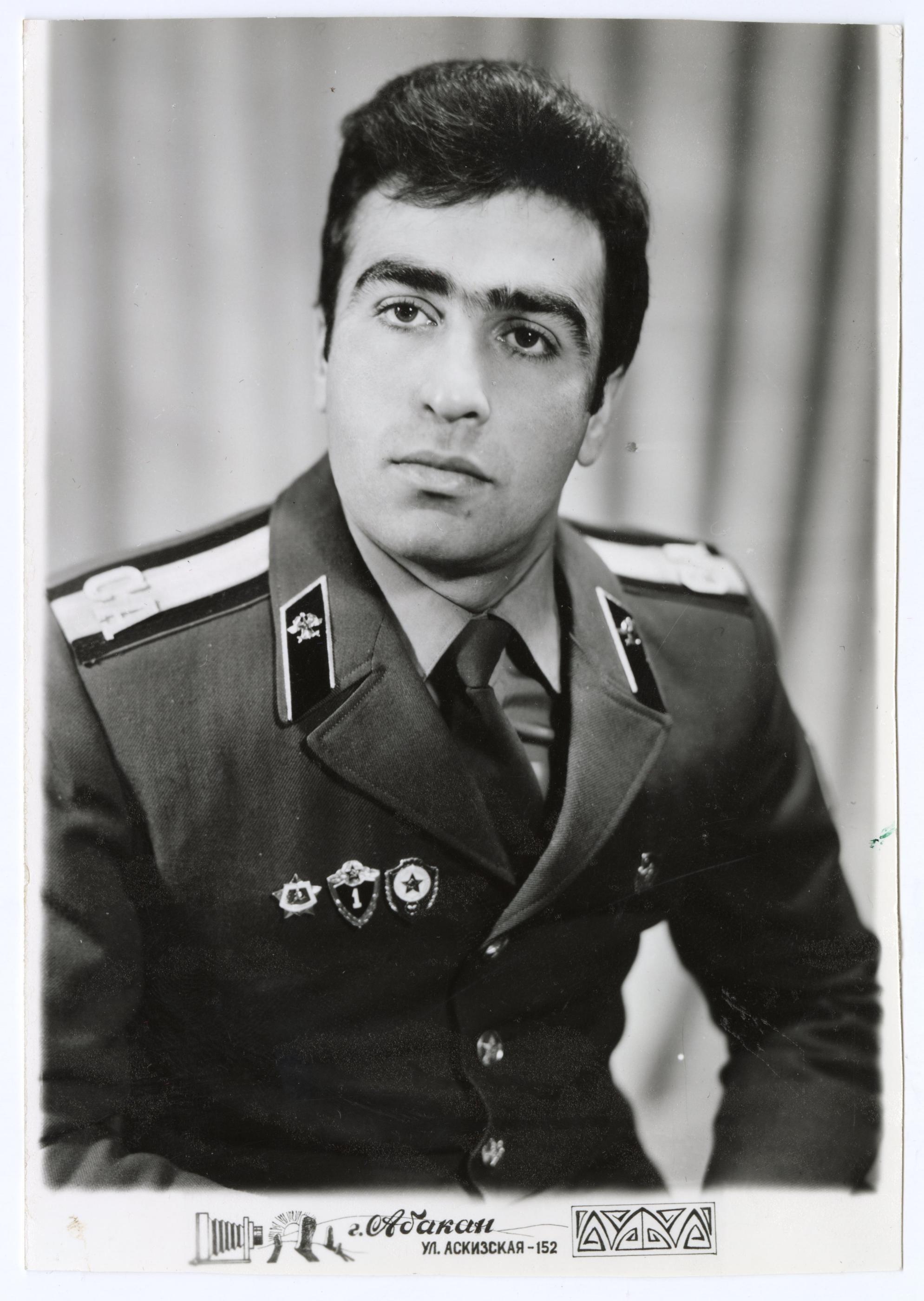

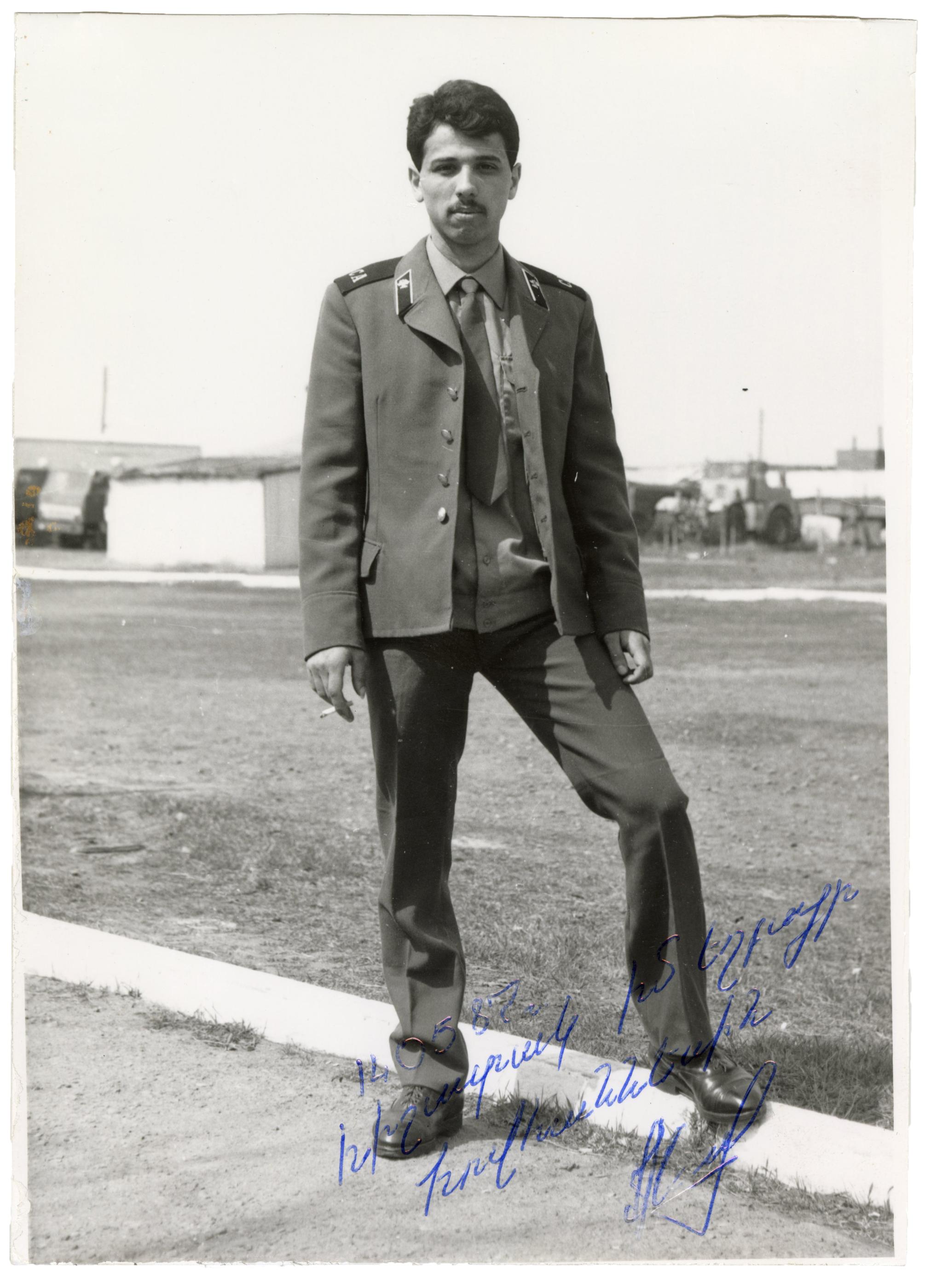

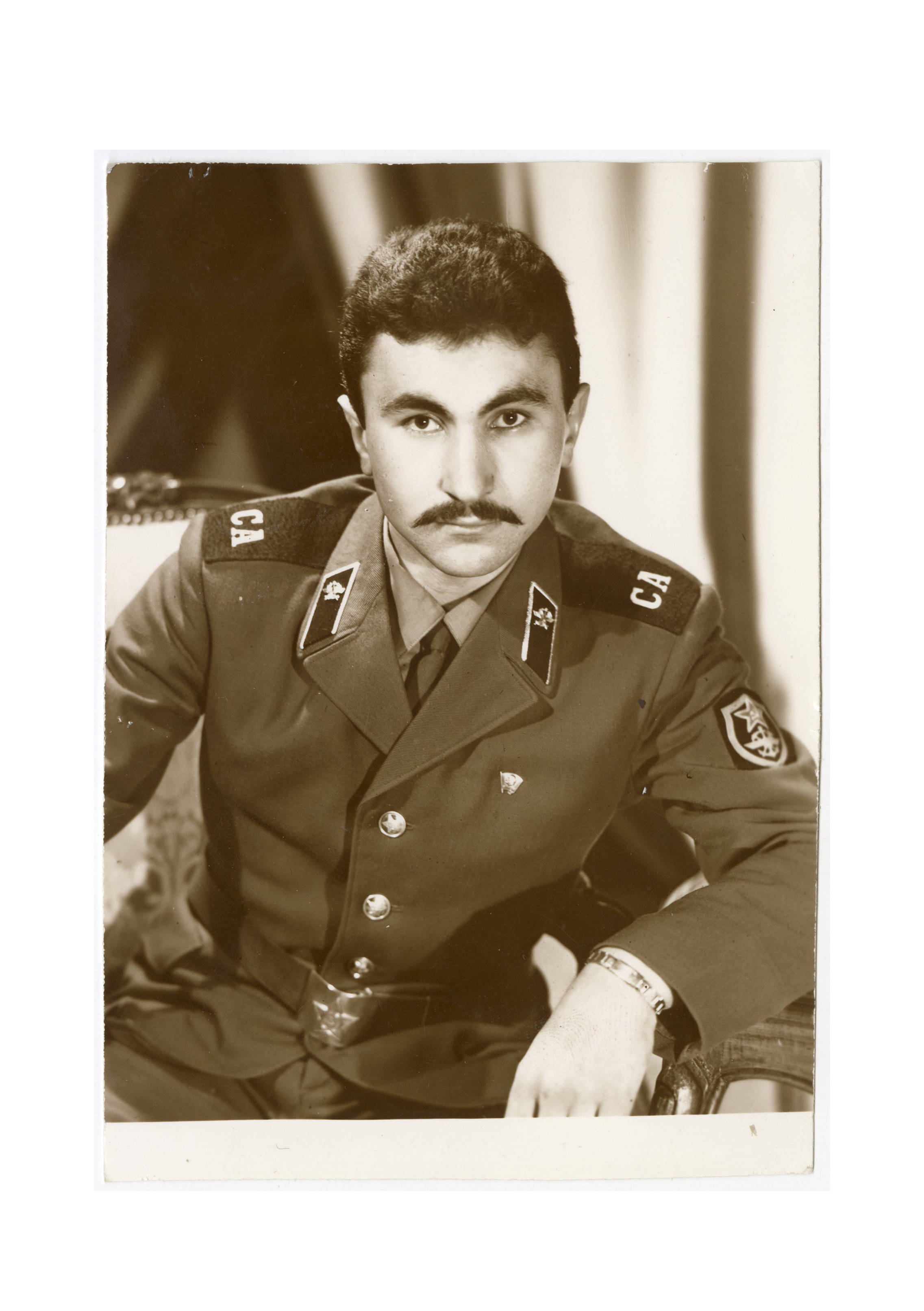

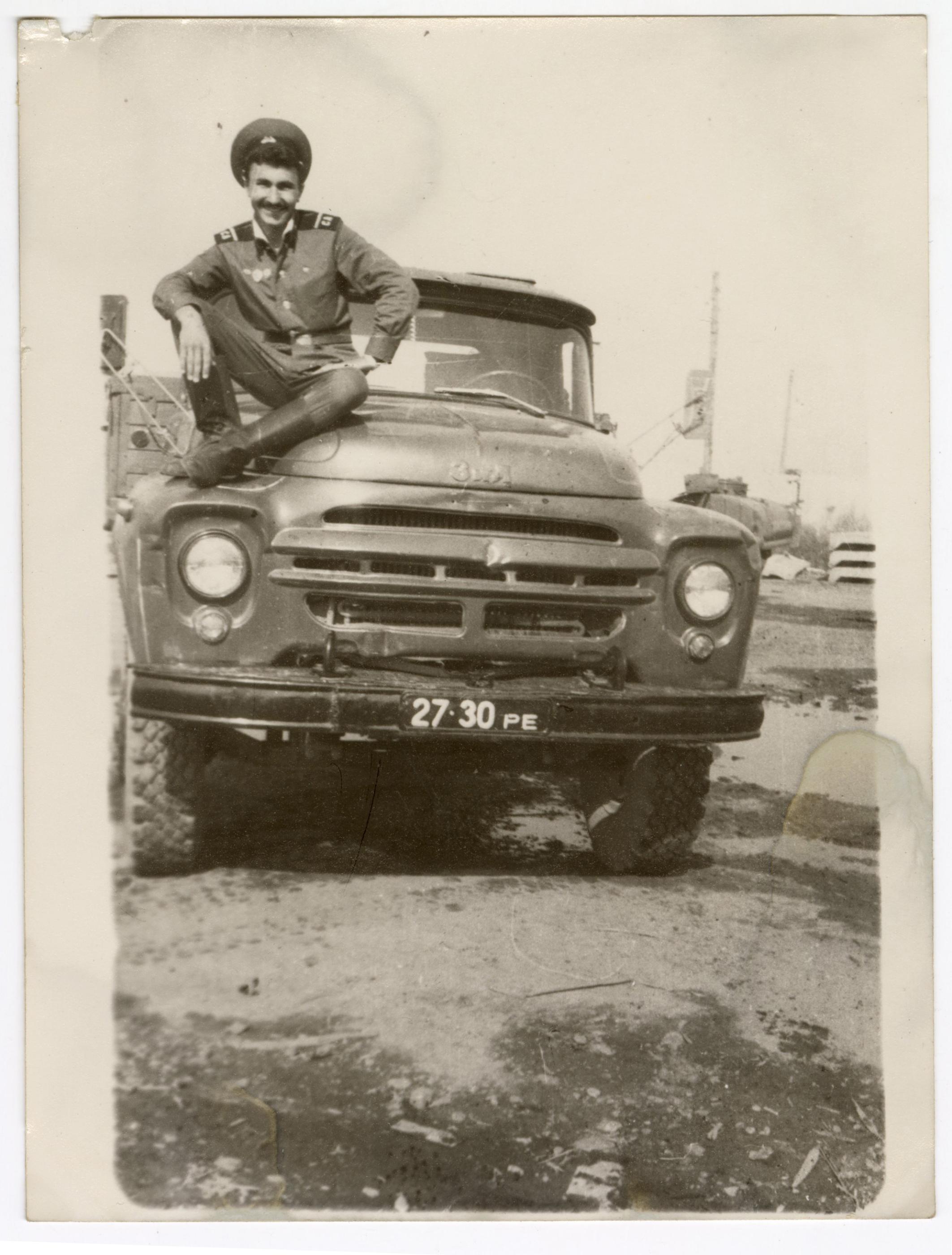

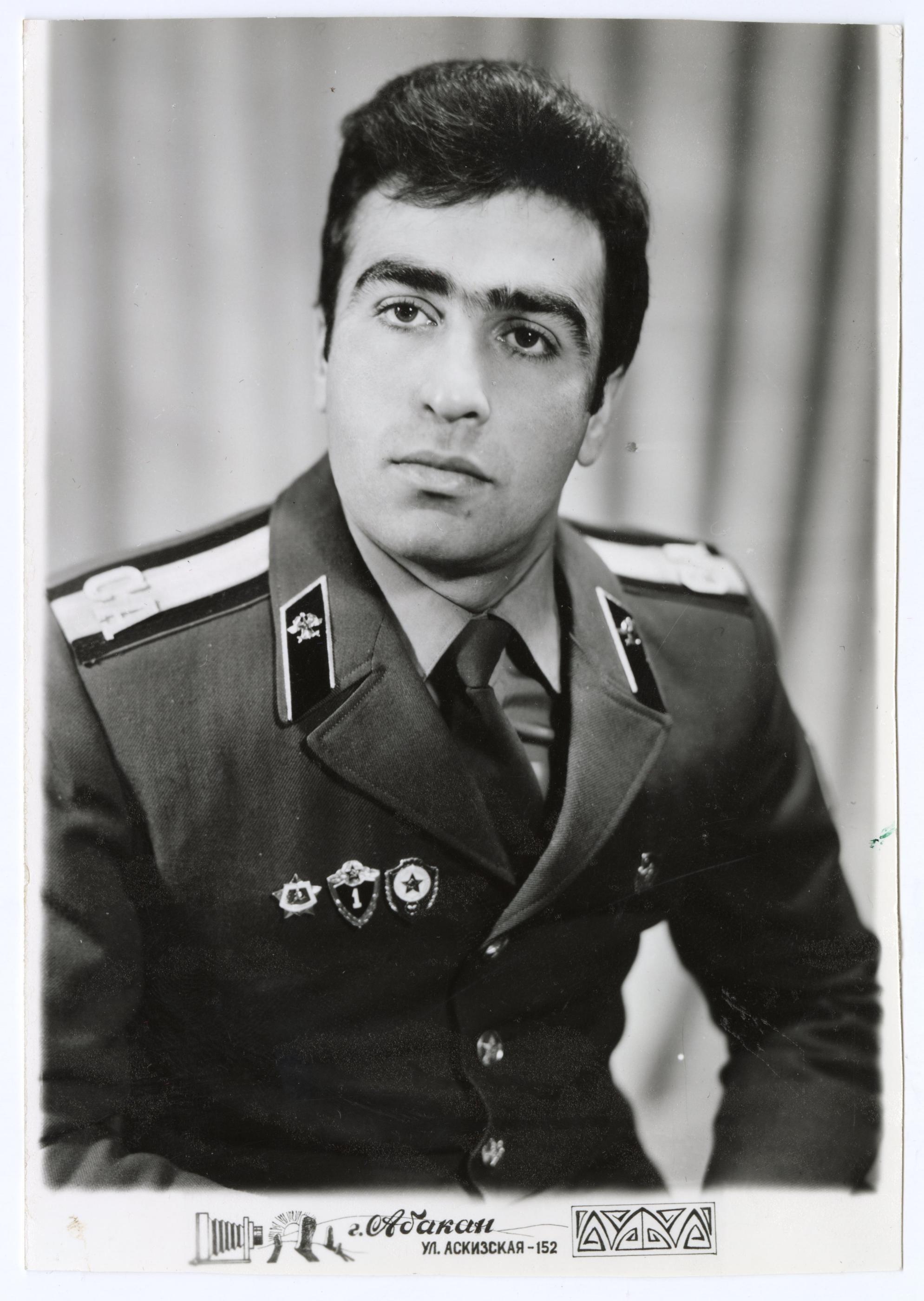

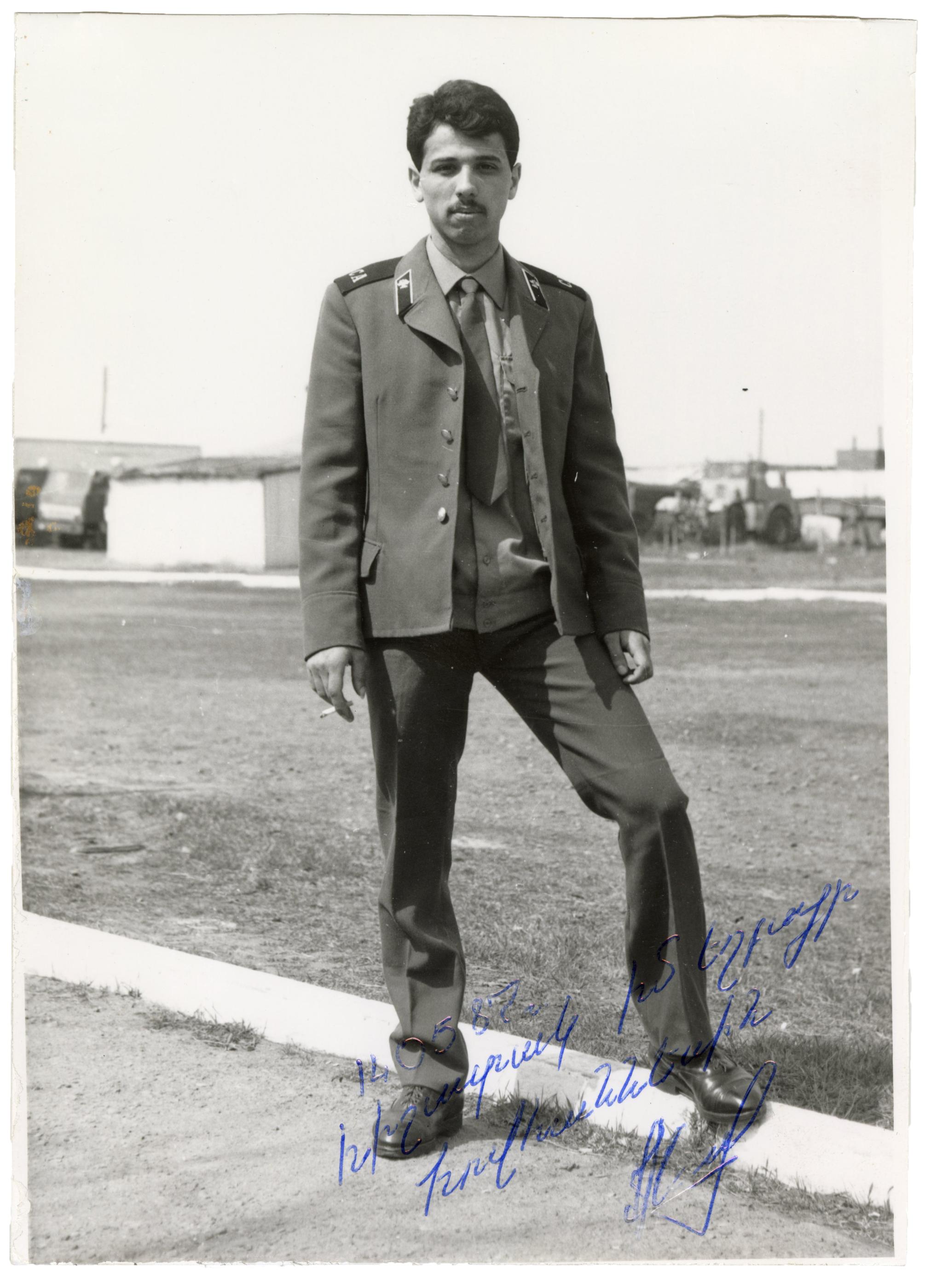

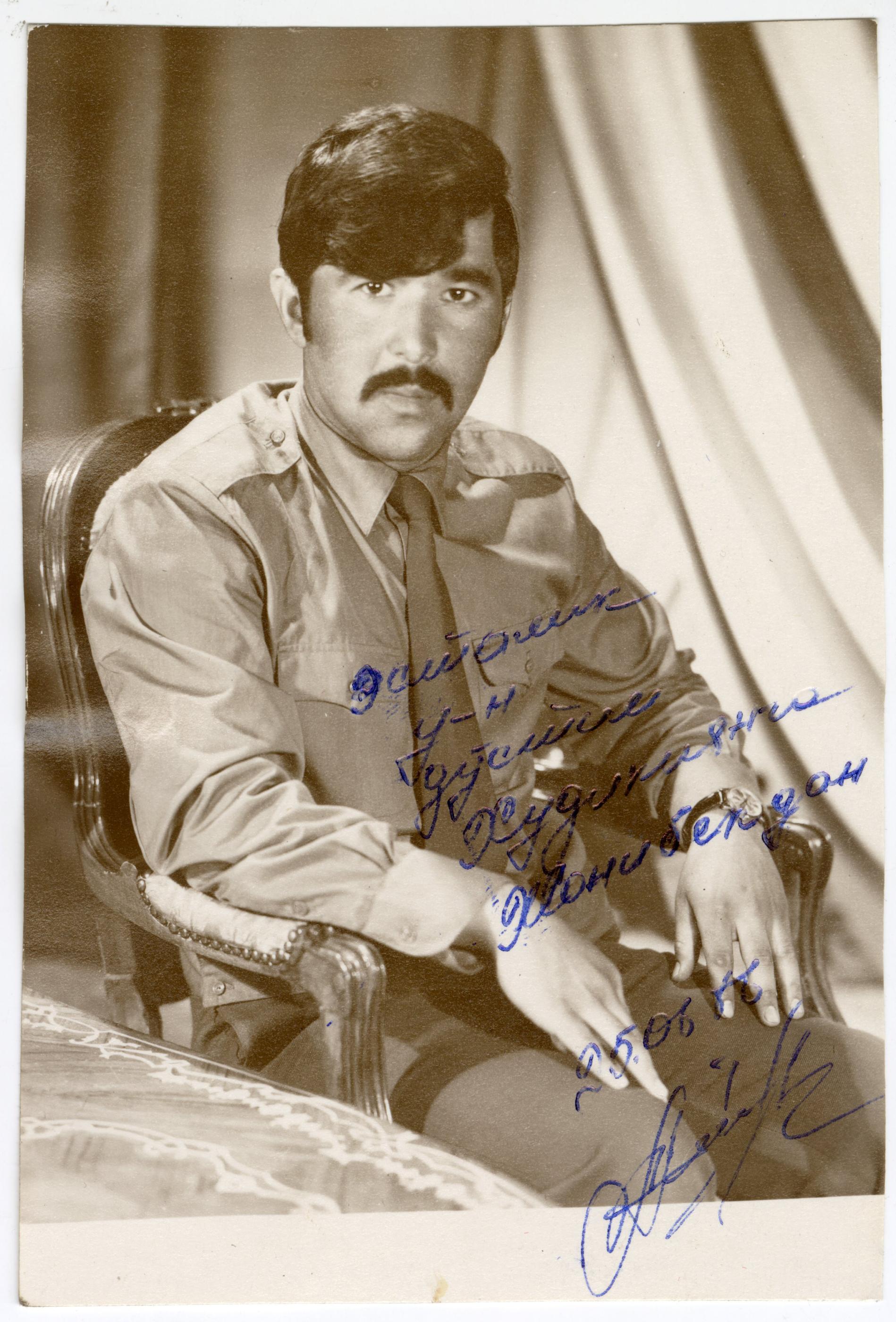

It is 2014 and I am taking a class in Russian History. Today, I learned of the secret stores and taboo imports that were reserved exclusively for the nomenclature, the elite class, the devout Communists. I ask my father if this is true. Did they exist? He says yes. He tells me of the imported fabrics from Europe, the superior quality of food and clothing that were only for them. How do you know? He tells me, somewhere in the boxes in the basement, there is a book of photographs. He says he made it. He says, I know... because I was one of them.

I run downstairs and rummage through towering boxes for some time. It is not until I have my hands gripped around the book that I finally take a breath. I run my hands along the surface: A soft, brown velveteen. I pause upon two layers of felt that have been glued together--a hammer and sickle. I open it. And I disappear into a life that is unlike my own.

I run downstairs and rummage through towering boxes for some time. It is not until I have my hands gripped around the book that I finally take a breath. I run my hands along the surface: A soft, brown velveteen. I pause upon two layers of felt that have been glued together--a hammer and sickle. I open it. And I disappear into a life that is unlike my own.

My father says he can still draw the face of Lenin from memory. He tells me it was part of his practice while in art school during that time. He was once an accomplished painter and figure drawing artist. Then came the Soviet Army. He became a high-ranking Lieutenant.

And even as a communist, he never stopped creating. He continued to draw and commissioned portraits of his friends. He bound the pages into a book. Together, they are enveloped in a brown velveteen, as if cut from the fabric of his own uniform. Inside, there are penned notes from his dear comrades. Their faces, mere black and white reveries of themselves. Their eyes, riddled by the crimson red veil that once cloaked their vision for 71 long years.

And even as a communist, he never stopped creating. He continued to draw and commissioned portraits of his friends. He bound the pages into a book. Together, they are enveloped in a brown velveteen, as if cut from the fabric of his own uniform. Inside, there are penned notes from his dear comrades. Their faces, mere black and white reveries of themselves. Their eyes, riddled by the crimson red veil that once cloaked their vision for 71 long years.

дорогой товарищ

Ongoing: Through family archives, current photos, and written letters, I trace the generational trauma and ideological influence of Soviet Armenia that continues to plague the minds of many Armenians within and beyond their homeland.

Like many post-soviet countries, the environment of Armenia has become a reflection of not only the conflicts that have taken place on the surface, but also in the hearts and minds of its people. Structures from the Soviet era still remain: Grand, Brutalist architecture that once dominated the lands have lost their guise of wealth. Abandoned buildings, worn cars, and dilapidated bunkers are reminders of an era that instilled scarcity and fear. These cold, authoritarian Russian ruins bare a stark contrast to the rich, warm sights that represent an ancient, early Christian Armenia.

Ongoing: Through family archives, current photos, and written letters, I trace the generational trauma and ideological influence of Soviet Armenia that continues to plague the minds of many Armenians within and beyond their homeland.

Like many post-soviet countries, the environment of Armenia has become a reflection of not only the conflicts that have taken place on the surface, but also in the hearts and minds of its people. Structures from the Soviet era still remain: Grand, Brutalist architecture that once dominated the lands have lost their guise of wealth. Abandoned buildings, worn cars, and dilapidated bunkers are reminders of an era that instilled scarcity and fear. These cold, authoritarian Russian ruins bare a stark contrast to the rich, warm sights that represent an ancient, early Christian Armenia.

I

мама

The year is 2025 and the war is not yet over. My mother has not returned to her country since she left in 1990, before the fall of the Soviet Union. When I asked her if she would ever go back she was quick to say no. She says she will never forget when she was surrounded by the tanks, the guns, and the barricades.

She was still pregnant with my sister then. Her birth was complicated. She says the doctors there are no good. She says that could be why my sister turned out the way she did.

She was still pregnant with my sister then. Her birth was complicated. She says the doctors there are no good. She says that could be why my sister turned out the way she did.

II

папа

It is 2014 and I am taking a class in Russian History. Today, I learned of the secret stores and taboo imports that were reserved exclusively for the nomenclature, the elite class, the devout Communists. I ask my father if this is true. Did they exist? He says yes. He tells me of the imported fabrics from Europe, the superior quality of food and clothing that were only for them. How do you know? He tells me, somewhere in the boxes in the basement, there is a book of photographs. He says he made it. He says, I know... because I was one of them.

I run downstairs and rummage through towering boxes for some time. It is not until I have my hands gripped around the book that I finally take a breath. I run my hands along the surface: A soft, brown velveteen. I pause upon two layers of felt that have been glued together--a hammer and sickle. I open it. And I disappear into a life that is unlike my own.

I run downstairs and rummage through towering boxes for some time. It is not until I have my hands gripped around the book that I finally take a breath. I run my hands along the surface: A soft, brown velveteen. I pause upon two layers of felt that have been glued together--a hammer and sickle. I open it. And I disappear into a life that is unlike my own.

My father says he can still draw the face of Lenin from memory. He tells me it was part of his practice while in art school during that time. He was once an accomplished painter and figure drawing artist. Then came the Soviet Army. He became a high-ranking Lieutenant.

And even as a communist, he never stopped creating. He continued to draw and commissioned portraits of his friends. He bound the pages into a book. Together, they are enveloped in a brown velveteen, as if cut from the fabric of his own uniform. Inside, there are penned notes from his dear comrades. Their faces, mere black and white reveries of themselves. Their eyes, riddled by the crimson red veil that once cloaked their vision for 71 long years.

And even as a communist, he never stopped creating. He continued to draw and commissioned portraits of his friends. He bound the pages into a book. Together, they are enveloped in a brown velveteen, as if cut from the fabric of his own uniform. Inside, there are penned notes from his dear comrades. Their faces, mere black and white reveries of themselves. Their eyes, riddled by the crimson red veil that once cloaked their vision for 71 long years.

дорогой товарищ

Ongoing: Through family archives, current photos, and written letters, I trace the generational trauma and ideological influence of Soviet Armenia that continues to plague the minds of many Armenians within and beyond their homeland.

Like many post-soviet countries, the environment of Armenia has become a reflection of not only the conflicts that have taken place on the surface, but also in the hearts and minds of its people. Structures from the Soviet era still remain: Grand, Brutalist architecture that once dominated the lands have lost their guise of wealth. Abandoned buildings, worn cars, and dilapidated bunkers are reminders of an era that instilled scarcity and fear. These cold, authoritarian Russian ruins bare a stark contrast to the rich, warm sights that represent an ancient, early Christian Armenia.

Ongoing: Through family archives, current photos, and written letters, I trace the generational trauma and ideological influence of Soviet Armenia that continues to plague the minds of many Armenians within and beyond their homeland.

Like many post-soviet countries, the environment of Armenia has become a reflection of not only the conflicts that have taken place on the surface, but also in the hearts and minds of its people. Structures from the Soviet era still remain: Grand, Brutalist architecture that once dominated the lands have lost their guise of wealth. Abandoned buildings, worn cars, and dilapidated bunkers are reminders of an era that instilled scarcity and fear. These cold, authoritarian Russian ruins bare a stark contrast to the rich, warm sights that represent an ancient, early Christian Armenia.

I

мама

The year is 2025 and the war is not yet over. My mother has not returned to her country since she left in 1990, before the fall of the Soviet Union. When I asked her if she would ever go back she was quick to say no. She says she will never forget when she was surrounded by the tanks, the guns, and the barricades.

She was still pregnant with my sister then. Her birth was complicated. She says the doctors there are no good. She says that could be why my sister turned out the way she did.

She was still pregnant with my sister then. Her birth was complicated. She says the doctors there are no good. She says that could be why my sister turned out the way she did.

II

папа

It is 2014 and I am taking a class in Russian History. Today, I learned of the secret stores and taboo imports that were reserved exclusively for the nomenclature, the elite class, the devout Communists. I ask my father if this is true. Did they exist? He says yes. He tells me of the imported fabrics from Europe, the superior quality of food and clothing that were only for them. How do you know? He tells me, somewhere in the boxes in the basement, there is a book of photographs. He says he made it. He says, I know... because I was one of them.

I run downstairs and rummage through towering boxes for some time. It is not until I have my hands gripped around the book that I finally take a breath. I run my hands along the surface: A soft, brown velveteen. I pause upon two layers of felt that have been glued together--a hammer and sickle. I open it. And I disappear into a life that is unlike my own.

I run downstairs and rummage through towering boxes for some time. It is not until I have my hands gripped around the book that I finally take a breath. I run my hands along the surface: A soft, brown velveteen. I pause upon two layers of felt that have been glued together--a hammer and sickle. I open it. And I disappear into a life that is unlike my own.

My father says he can still draw the face of Lenin from memory. He tells me it was part of his practice while in art school during that time. He was once an accomplished painter and figure drawing artist. Then came the Soviet Army. He became a high-ranking Lieutenant.

And even as a communist, he never stopped creating. He continued to draw and commissioned portraits of his friends. He bound the pages into a book. Together, they are enveloped in a brown velveteen, as if cut from the fabric of his own uniform. Inside, there are penned notes from his dear comrades. Their faces, mere black and white reveries of themselves. Their eyes, riddled by the crimson red veil that once cloaked their vision for 71 long years.

And even as a communist, he never stopped creating. He continued to draw and commissioned portraits of his friends. He bound the pages into a book. Together, they are enveloped in a brown velveteen, as if cut from the fabric of his own uniform. Inside, there are penned notes from his dear comrades. Their faces, mere black and white reveries of themselves. Their eyes, riddled by the crimson red veil that once cloaked their vision for 71 long years.